13 Investigates: High Use in the High Peaks Part I

[anvplayer video=”4970887″ station=”998132″]

KEENE — Hiking in the Adirondacks seems to be more popular than ever. 12 million people visit the Adirondack park every year. That’s more than Acadia, Yellowstone, and Yosemite combined. That was before the pandemic. After this summer season, some groups say we are at a tipping point, and we must act now to save our forests.

If you’ve driven from the Northway to Lake Placid, you’ve seen it: Mountain above, long line of cars parked on the roadside below. Route 73 has a parking problem.

Even the “no parking” signs at Giant Mountain don’t completely stop people. Drivers will just take the ticket. This past holiday weekend, a long line of cars had tickets in that no-parking zone. Throughout the entire Route 73 corridor last weekend, the DEC says about 150 cars received tickets.

That’s the road safety problem, we wanted to see the impact on the trail first hand.

We met Tyler Socash at the trailhead of Cascade Mountain, on a weekday after Labor Day in early September.

If the tattered and torn trail register is any indication, Cascade is a popular peak. According to the latest data, nearly 35 thousand people hiked it in 2016. That’s more than double the amount a decade before.

Socash works with the Adirondack Mountain Club, educating hikers on being more responsible. He’s an accomplished hiker himself. Outside of the Blue Line, Socash has hiked the Appalachian Trail, the Pacific Crest Trail, and the Te Araroa Trail in New Zealand.

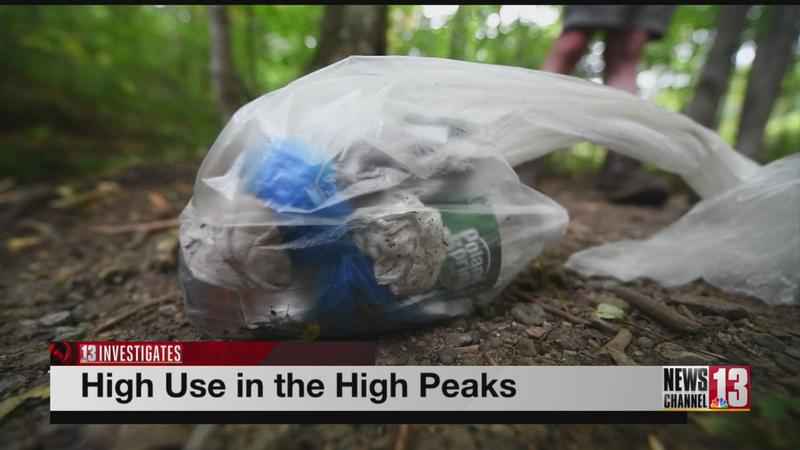

Nowadays in the Adirondacks, he brings a garbage bag on each hike, picking up other people’s trash.

On our hike, Socash found face wipes, a bag from a dog owner, orange peels, and a sign of the times: face masks.

Socash also deals with something else: toilet paper. We saw lots and lots of it on our hike up Cascade. Socash buries it, when people leave it.

There’s that impact, then there’s erosion. Hundreds of thousands of boot steps do damage over time.

The trail gets lower, and big rocks and roots emerge. That makes hiking the trail tougher. People venture off it, just a little bit, making it wider and wider.

How wide?

A photo from the Adirondack Council from the 1980s on Cascade shows how one part of the trail grew to 25 feet in 2018.

The issue of trail erosion has been talked about for decades in the Adirondacks. The DEC said this in its High Peaks Unit Management Plan, published in 1999:

"Most trail problems are the result of poor trail location and improper construction and maintenance rather than the amount of use. Some trails are over 100 years old and were initially located to achieve the shortest distance between two points or where construction was easy. Their poor location often makes erosion control difficult."

There is a reason for all those hikers. When you get to the top, all 4 thousand and 98 feet, it is glorious.

“They want to get outside, they want to have fun, they want to have an opportunity to see some wildlife. And maybe to experience those intangibles of wildness,” said Socash.

“I’ve noticed during the pandemic there are a lot of user groups coming to the Adirondack Park, which is fantastic,” said Socash. “…The thing I’m noticing is most people are just a bit unprepared and many of them are biting off a little bit more than they can chew.”

“When I summit steward on Mount Marcy, one of the most remote places in New York State, I’m often told this exact sentence: ‘this is my first hike in the Adirondacks.’ And i think, ‘wow, you’ve chosen to hike a marathon before your first 5k.’”

Those are some of the problems, so what can be done? That is the next part of the story, which you can watch here.