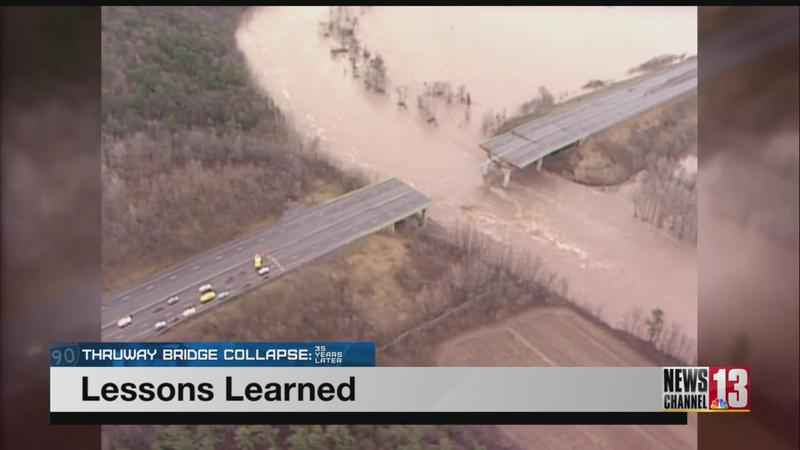

Lessons learned from the Schoharie Creek Thruway bridge collapse

In the 35 years since the Schoharie Creek Thruway bridge collapse, there’s been changes in bridge design and inspection regulations.

According National Transportation Safety Board report after the collapse, water ate away at the underwater supports of the Thruway bridge, eventually sending it careening into the creek below.

Mike Elmendorf, president and CEO of Associated General Contractors, said his company works closely with the state to help maintain bridges – a practice that changed after the Schoharie Creek bridge collapse.

“The state of New York certainly — I think — it took a lot of lessons from that terrible tragedy,” Elmendorf said.

After that collapse, Congress acted to require yearly reports called Graber Reports. The latest one is from the 2018-2019 fiscal year.

The Federal Highway Administration said Congress gave the agency more power to require underwater inspection of bridges.

“When it comes to waterways prior to the collapse of Schoharie Creek, you were allowed to put a footing on hard packed soil, not necessarily rock,” Vice President of Transportation Services at AGC Sarah Patrie said. “If there’s anything that we learned from this bridge collapse — and engineering in general — it’s that water is a very powerful force.”

Patrie added there was confusion back then there wouldn’t be now.

In the NTSB report of the bridge collapse, it cited "ambiguous plans."

Patrie told us in an email:

“Not only is the design process as a whole more rigorous now — especially in waterways — but in watching old videos from the collapse, it seems there was some ambiguity in the intent of the design that the contractor had to interpret. That would never happen now; there are multiple engineers and levels of management that would assist in clarification of the design of a structure, and major inspection and approval of the construction process itself."

She adds now, engineers are moving into 3D modeling of construction process to show if bridge designs are up to par.

“With that, you can model these different weather events and make sure that the design you’re doing is going to be safe for any sort of 100 year storm, 150 year storm, 200 years storm,” Patrie said.

We reached out to the Department of Transportation for comment. It denied us an interview several times, but sent us a statement with the same info Elmendorf and Patrie provided.